We’re at the end of 2012, a year many of us will remember less than fondly if for no other reason the politico/economic foibles in both the US and Europe. Call it “The Year of Class Warfare” if you like, economically speaking. We should also remember it as a very important transitional year, and if we need a name for it in the tech space, I suggest “The Year of the Cannibal.”

There’s lots of talk about technology, new technology, for 2013. We have carrier WiFi and Ethernet, we have virtual networking and SDN, we have good old cloud computing and virtualization. Articles speculate about 100G Ethernet, vectored DSL, and other developments, but what gets missed all too often is that these trends are driven not by new revenue opportunity but by cost management. The challenge of our industry is that we’ve missed the boat on benefits.

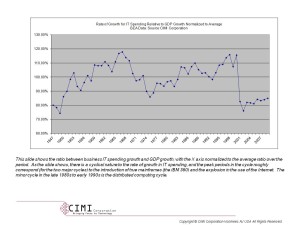

We did a study for Wall Street years ago on how growth in IT investment and GDP growth related. Most people would think intuitively that the result was the good old marketing hockey stick, an exponential explosion. It’s not, it’s a sine wave. What the chart below

shows is that we’ve had periods (cycles, if you will) where some factor drove IT investment to rise much faster than GDP, and other periods when its sunk below the long term average, which is our baseline for this chart. If I go back to our surveys for the period since 1982 I can glean the primary causal data on this phenomenon; we find new paradigms to drive productivity growth and so unlock a new set of benefits. As companies exploit these new paradigms to garner some much-needed ROI, they drive spending faster than historical averages. If you look at the timing of these cycles you see that they roughly coincide with the advent of distributed computing and the Internet, certainly two things that have changed our perception of the value of technology.

Look now at the end of the chart. We hit a big bottom coincident with the NASDAQ crash, the “bursting of the tech bubble” in the late 1990s, and since then we’ve been unable to muster anything convincing to drive up the rate of IT spending relative to GDP. We’re now hovering at about 85% of historical levels, meaning that IT GROWTH is expanding slower than GDP growth is. Remember, this chart shows rate of change in GROWTH, and it shows that when productivity value is on the table we accelerates the rate at which IT spending grows. It’s not been on the table, and that’s what makes this the Year of the Cannibal. “Growth” comes from eating somebody else’s share. Eventually everything gets eaten.

This is the challenge that faces the vendors in 2013, and that faces “new technologies” in 2013 as well. If the cloud, if SDN, represents nothing but a reduction in costs then these new things will erode the TAM for everything in tech and we’ll become cheap as dirt. If these developments advance the VALUE of technology, by improving productivity and driving benefits upward, then we can have another of those waves of growth—a wave that’s already long overdue.